Memex paper of Vannevar Bush, in 1945, predicted, or maybe better said inspired the computer revolution. Doug Engelbart said it was seminal to him. It is worth reading again. These are my notes on reading it from the point of view of “how are we doing towards it?” (scanned copy from Life Magazine condensed version)

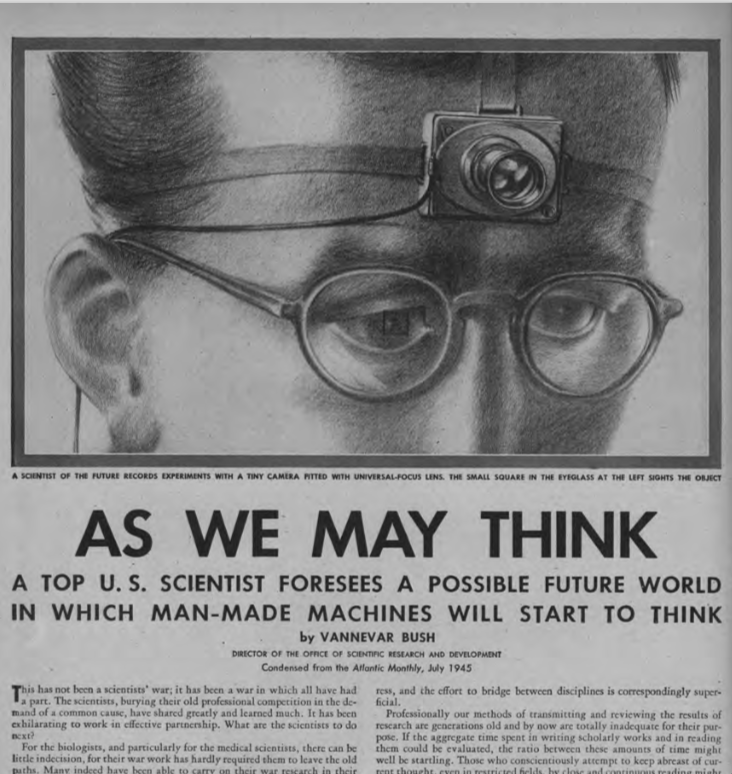

Photograph everything interesting one sees, but high rez. Television for seeing these static images at a distance.

10,000 : 1 compression by microfilming. Encyclopaedia Britannica is size of a matchbook, a million book library in an end of a desk. (The web, Internet Archive, Google books)

Create faster by text-to-speech; “read” by speech-to-text. (Siri)

Augmenting intellegence with computation: “For mature thought there is no mechanical substitute. But creative thought and essentially repetitive thought are very different things. For the latter there are, and may be, powerful mechanical aids.” — hum, creative thought might be mechanically substituted?

Predicted general purpose computers… “Such machines will have enormous appetites. One of them will take instructions and data from a whole roomful of girls armed with simple key board punches, and will deliver sheets of computed results every few minutes. There will always be plenty of things to compute in the detailed affairs of millions of people doing complicated things.”

Machines to do higher logic and math. (Mathmatica)

Search: “The prime action of use is selection, and here we are halting indeed. There may be millions of fine thoughts, and the account of the experience on which they are based, all encased within stone walls of acceptable architectural form; but if the scholar can get at only one a week by diligent search, his syntheses are not likely to keep up with the current scene.

Selection, in this broad sense, is a stone adze in the hands of a cabinetmaker. “ (Google search)

Better than indexing, association “Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing. … The human mind does not work that way. It operates by association. … Yet the speed of action, the intricacy of trails, the detail of mental pictures, is awe-inspiring beyond all else in nature. “ (relevance feedback, original Alexa Internet idea, related links)

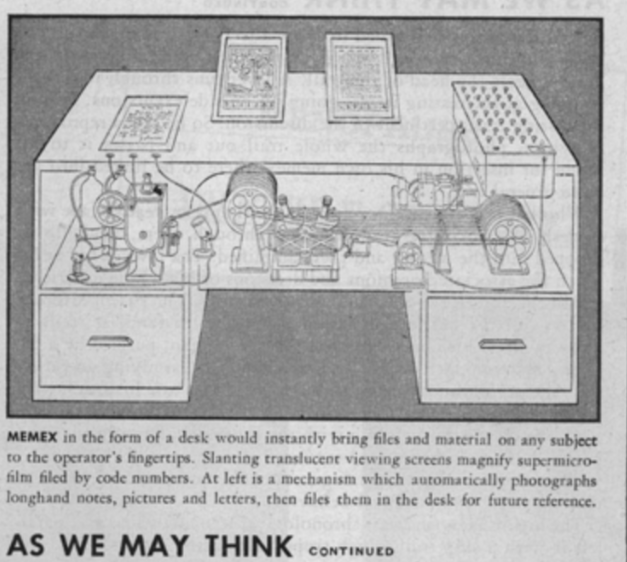

The Memex: “Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, ‘memex’ will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.

It consists of a desk, and while it can presumably be operated from a distance, it is primarily the piece of furniture at which he works. On the top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. There is a keyboard, and sets of buttons and levers. Otherwise it looks like an ordinary desk.

Personal, corporate, and wide area information integrated (WAIS concepts paper, Web, Google Drive): “Most of the memex contents are purchased on microfilm ready for insertion. Books of all sorts, pictures, current periodicals, newspapers, are thus obtained and dropped into place. Business correspondence takes the same path. And there is provision for direct entry. On the top of the memex is a transparent platen. On this are placed longhand notes, photographs, memoranda, all sorts of things. When one is in place, the depression of a lever causes it to be photographed onto the next blank space in a section of the memex film, dry photography being employed.”

Flipping through pages on a screen: “On deflecting one of these levers to the right he runs through the book before him, each page in turn being projected at a speed which just allows a recognizing glance at each. If he deflects it further to the right, he steps through the book 10 pages at a time; still further at 100 pages at a time. Deflection to the left gives him the same control backwards.”

Annotation (not done yet, hypothosis): “He can add marginal notes and comments, taking advantage of one possible type of dry photography, and it could even be arranged so that he can do this by a stylus scheme, such as is now employed in the telautograph seen in railroad waiting rooms, just as though he had the physical page before him.”

Linking is the important thing: “All this is conventional, except for the projection forward of present-day mechanisms and gadgetry. It affords an immediate step, however, to associative indexing, the basic idea of which is a provision whereby any item may be caused at will to select immediately and automatically another. This is the essential feature of the memex. The process of tying two items together is the important thing.”

Annotating with links (not done yet): “The user taps a single key, and the items are permanently joined. “

Following a link with one action: “Thereafter, at any time, when one of these items is in view, the other can be instantly recalled merely by tapping a button below the corresponding code space. “

Surfing: “The owner of the memex, let us say, is interested in the origin and properties of the bow and arrow. Specifically he is studying why the short Turkish bow was apparently superior to the English long bow in the skirmishes of the Crusades. He has dozens of possibly pertinent books and articles in his memex. First he runs through an encyclopedia, finds an interesting but sketchy article, leaves it projected. Next, in a history, he finds another pertinent item, and ties the two together. Thus he goes, building a trail of many items. Occasionally he inserts a comment of his own, either linking it into the main trail or joining it by a side trail to a particular item. When it becomes evident that the elastic properties of available materials had a great deal to do with the bow, he branches off on a side trail which takes him through textbooks on elasticity and tables of physical constants. He inserts a page of longhand analysis of his own. Thus he builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him.”

Leveraging past trails, passing them to others, adding them to the memex (Alexa Internet’s original vision, not done yet) “The owner of the memex, let us say, is interested in the origin and properties of the bow and arrow. Specifically he is studying why the short Turkish bow was apparently superior to the English long bow in the skirmishes of the Crusades. He has dozens of possibly pertinent books and articles in his memex. First he runs through an encyclopedia, finds an interesting but sketchy article, leaves it projected. Next, in a history, he finds another pertinent item, and ties the two together. Thus he goes, building a trail of many items. Occasionally he inserts a comment of his own, either linking it into the main trail or joining it by a side trail to a particular item. When it becomes evident that the elastic properties of available materials had a great deal to do with the bow, he branches off on a side trail which takes him through textbooks on elasticity and tables of physical constants. He inserts a page of longhand analysis of his own. Thus he builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him.”

Wikipedias: “Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified. “

Alternative assemblages, ala Ted Nelson’s ZigZag: “The historian, with a vast chronological account of a people, parallels it with a skip trail which stops only on the salient items, and can follow at any time contemporary trails which lead him all over civilization at a particular epoch. “

Editors, ala WAIS Concepts Paper (not done yet), somewhat done with tweets, facebook, (but no backlinks): “There is a new profession of trail blazers, those who find delight in the task of establishing useful trails through the enormous mass of the common record. “

Telepathy (openwater) and VR: “All our steps in creating or absorbing material of the record proceed through one of the senses—the tactile when we touch keys, the oral when we speak or listen, the visual when we read. Is it not possible that some day the path may be established more directly?”

Dealing with information overload: “Presumably man’s spirit should be elevated if he can better review his shady past and analyze more completely and objectively his present problems. He has built a civilization so complex that he needs to mechanize his records more fully if he is to push his experiment to its logical conclusion and not merely become bogged down part way there by overtaxing his limited memory. “

Weilding this technology for good rather than conflict: “The applications of science have built man a well-supplied house, and are teaching him to live healthily therein. They have enabled him to throw masses of people against one another with cruel weapons. They may yet allow him truly to encompass the great record and to grow in the wisdom of race experience. He may perish in conflict before he learns to wield that record for his true good. Yet, in the application of science to the needs and desires of man, it would seem to be a singularly unfortunate stage at which to terminate the process, or to lose hope as to the outcome.”

The As We May Think seemed to come out nowhere, with such as complete and foundational picture of how these systems would work together. Has anyone traced the linage of these ideas. It is still is one of those epic papers.

My recollections (from my autobiography, POSSIPLEX)–

What would Vannevar Bush have said? ca. 1968

I believe I read Bush’s “As We May Think” when it came out in 1945– twice, indeed; first in The Atlantic, which I think was read aloud around the Saturday lunch table at our farm; and then when it was reprinted in LIFE. (Since I was eight when it came out, there is no knowing, but my family subscribed to both magazines and the article was certainly on my wavelength.)

In the Vassar days of the mid-sixties, as I stepped up my computer reading, I found the article cited repeatedly in the artificial-intelligence literature, to which it was supremely irrelevant. But I cited it in my foundational hypertext articles, and it became the semi-official Beginning of the Hypertext Field.

In 1968, I think it was, I was at the Spring Joint Computer Conference in Boston [correction: that was 1966]. I got a handful of change and picked up the payphone and simply called information. Vannevar Bush was listed in some Boston suburb. He himself answered the phone.

I told him I was working on ideas similar to his memex and would like to get together with him to discuss it on some later trip.

He wanted very much to discuss it with me, he said.

But I hated him instantly. He sounded like a sports coach. I knew I would not follow up, even if I managed to get to Boston again.

=== Now I am very sorry, of course.

But we do what we do, and emotions prevail.

The As We May Think seemed to come out nowhere, with such as complete and foundational picture of how these systems would work together. Has anyone traced the linage of these ideas. It is still is one of those epic papers.