Brewster Kahle

January 9, 2012

On archive.org.

The largest single expense for the staff of the Internet Archive is housing, as this paper will show the majority of the cost of housing goes to debt service (either directly through mortgage, or indirectly through rent). If employees could live in debt-free housing, then their expenses would go down and sense of security could go up. This paper explains why this might be a good idea not only for the Internet Archive employees, but for all workers in public-benefit non-profit organizations and goes on to suggest how to start a system of debt-free housing.

Some say they are in a “Debt Trap”, and indeed they are– a cycle where debt piles on debt and becomes difficult to escape. The average household debt in just credit cards is over $15k and the average interest charged on this debt is over 13% per year[1]. Debt payments absorb between 11% and 24% of people’s incomes, depending on what is counted.[2] But if we pull back, there is a game, a “Debt Game” if you will, that has winners and losers. A well-designed game makes the winners think they deserve to win, and the losers feel that if they just try again they might just win. But it is important to know it is a game, because games have rules. These rules are made up, they are an invention, and so, in theory, they can be changed. Some people have become successful by expanding the Debt Game by creating new opportunities for people to get into debt: what was mainly debt from houses and farms then moved to car loans, then credit card debt and now student loans are propagating on an industrial scale. As some product or service type comes to be bought using debt by the majority of people it becomes more difficult to buy these things without debt because prices, terms, and regulations start to assume participation. But participation in this game is not always mandatory– there may be alternatives if we plan carefully. This paper will explore how we can opt out of some of the Debt Game by establishing enduring and transferable debt-free housing. Given that housing is the largest fraction of family debt, this could be a significant achievement, and one that could lead to further steps towards living debt-free.

Lets spend just a minute more on the debt game. The NY Times reported that the median family net worth (total assets minus total debts) the US is $70k and falling.[3] If we were to take away the house price support supplied by the Federal government through mortgage guarantees or federal mortgage purchase programs then we could find that already more than ½ of all households in the United States having a negative net worth, in other words, owe more than they own. Living in debt can increase family stress and psychological issues. Thus having ½ of all households having an effective negative net worth seems like a poor societal policy. But this might not be surprising if one considers where both money and debt come from: they are created from each other—when money is created, debt is created and when debt is paid off, money disappears. Many people do not realize this characteristic of money and debt, but it is important if we are to understand the nature of the Debt Game. With modern money, like the dollar, 95% of all money is created when banks make loans such as a mortgage. Here is how it works. A bank has to keep a small percentage of their deposits “in the bank” as a reserve, the rest can be lent. A bank customer who takes out a mortgage gets money to buy the house and a contract to pay it back over time. The money goes to the seller who then puts most of that money back into another bank. That bank has to keep the small fraction of their deposits on hand (historically 5%), and then can lend out the rest. But because most of the money they lend out gets redeposited into a bank somewhere, most of that money can be lent out again, thus for every 1 dollar originally created by the treasury through the federal reserve system, another 19 dollars in both debt and money can be created. This is called the fractional reserve system, and the more money there is the more debt there is as well, and vice versa. Since individuals or corporations can accumulate money without limit, and because households, in practice, are only allowed so much debt before they may not borrow any more, the number of debtors will tend to be more than creditors. Therefore the Debt Game has more losers than winners[4]. I mention this because it may inspire interest in alternatives, at least for life’s essentials such as food, housing, education, and health. This debt has real implications in people’s lives, and therefore could warrant our attention to create as positive a system as we can.

In a survey of the employees of the Internet Archive, housing turned out to be the largest expense for our employees (appendix A). For those that scan books in San Francisco for about two thousand five hundred dollars a month, they pay about half, or $1250, of their monthly gross income in rent. The programmers and head administrative staff are paid about three to ten thousand per month and rent or mortgage was often consumes 30% to 50% of their gross incomes. This is not restricted to just the high cost of housing in San Francisco. A 2011 Harvard study found that 49% of all renters paid above 30% of their income in rent[5]. For those in the income category of our scanners[6], 88% pay over 30% of their income, and 63% of them pay more than half of their income in rent. Say that again: 63% pay more than half of their income in rent, a level that is called “severely burdened” by the census department.

The same study showed that rents are increasing faster than incomes since 1980, which can bring a level of insecurity to an employee. Therefore, if we can find a way to decrease this expense and increase its price stability, then the employees might feel more secure and be able to accept the lower salary that often comes with non-profit work.

Those that own houses face the same issues, especially those on the coasts. Nationwide owners, including those without mortgages, 18% of them pay over 30% of their income for housing in 2007, and for those in the income category of our scanners, over 65% pay over 30% of their income[7]. And Californians pay a higher percentage than average Americans.

Housing cost, then, is a large burden on all workers, not just public benefit workers. But public-benefit workers have a special role in society, which should take extra care in protecting.

From a societal perspective, the time we most need public benefit workers is in recessions. Unfortunately many of the funding sources for public benefit organizations go through the same cycles as for-profit organizations but somewhat indirectly through taxes and philanthropies, which in turn are subject to the same business and investment cycles. If we can build a system that brings expense stability through down cycles for public benefit workers, or even build a counter-cyclical system thus supporting public benefit workers when for-profit workers need social services most, then we are building a more robust society.

If housing is such a large expense, why does it cost so much? It turns out about 75% of the cost of housing is in debt service, either directly through a mortgage, or indirectly through rent. To see this for homeowners, we can look at a couple of studies. For those that own, the census reports that seventy percent of all houses are mortgaged[8] and that same report states that “the median monthly housing costs for mortgaged homes in 2000 was $1,088; median housing costs for non-mortgaged houses was $295 per month.” Therefore about 75% of the cost of a mortgaged home related to the mortgage, and over 2/3rds of all houses are mortgaged. For rentals it is about the same 75%, but the calculation is a bit more involved. Rental buildings are priced to create a target return on capital, or “cap” rate of between 5% and 8% per year. In other words, the buildings are priced so that the return on the investment, after all expenses, is 5-8% annually. Other expenses, such as taxes and insurance are typically less than 3% (about 1% each for property tax and insurance and maintenance is typically a small percentage[9], therefore the “cost of money” or the cost of the debt is often over 66% and is typically 75% of the building cost (see attached spreadsheet). Even if the building is paid off, the prevailing market rents will pay the equivalent amount for the money, but instead of it going to a bank, it goes to the owner.

Therefore, housing costs could drop 75% if it were debt free. Sounds great, but how do we get there?

How to Create Debt Free Housing

With upfront investment, houses or apartments can be built or purchased outright to create debt-free housing, or possibly a set of distressed houses could be acquired, or a government program could create the basis of this system. While these approaches should be investigated, I will suggest a different approach that does not cost as much upfront nor depend on government intervention. This could work by transitioning market-based housing to debt-free housing over time with smaller upfront investment. In any case, we have to create binding by-laws that forbid future debts and liens being made on the property. That way if we can achieve debt-free status for some housing units, then they will stay that way even though it might benefit the current residents to incur a debt obligation. By-laws with such restrictions, if well forged, can endure especially if there is some independent entity or party to enforce the rule.

One way to finance the creation of debt-free housing units is to fund a non-profit organization to purchase a building with a mortgage and then to pay off the mortgage by renting to market-rate tenants. This approach creates debt-free housing units in the longer term, with the benefit that these units will be enduringly debt-free. A typical 30-year fixed-payment mortgage with a 20% down payment would be paid off in 30 years, but because inflation historically raises rents, taxes and maintenance costs while leaving the mortgage cost fixed, there will be a surplus generated by market-based renters before the full term of the loan. One use of the surplus could be to take out a second mortgage to refund the original down payment to the purchasing non-profit so that maybe it could use it to buy more properties to convert to debt-free housing. While this may seem unobvious to put a second mortgage on the building that is intended to be debt free, this can be seen as the last mortgage that structure will ever have. The point when a surplus is reached depends on future inflation, market conditions, building costs, and condition; but talking with one building owner, he has found that buildings turn profitable in 10 to 12 years.

Therefore starting in 10-12 years there can be enduringly subsidized housing, and by 30 years, all of the housing units will be debt free and therefore will have 75% less cost than the equivalent market-based rental unit.

Who would benefit from this housing? By this approach, it would be up to the purchasing organization. It could be used as a normal investment vehicle and generate cash rather than providing subsidizing housing. Another approach is to benefit a class of local residents, and in this case ones that work at selected public-benefit non-profit organizations.

If employees of a set of non-profits get access to these subsidized apartments, then it could help provide a significant job benefit and economic security against rising rents and rent fluctuations. If the houses were located close to the job then there could be advantages in commuting, and even build a community of shared resources among the co-workers that would not normally be developed in rental apartment buildings.

A potential disadvantage to the employee is that their apartment subsidy is tied to their employment and when they leave their job their subsidy will eventually go away. If the building is in a city then there will be other jobs and market-rate choices readily available, unlike some of the company towns built by mining companies a hundred years ago. Another disadvantage is that not all employees will want exactly the available subsidized housing. This could effect who would apply for jobs at the non-profit organizations.

This type of subsidized housing has existed for a long time for some larger non-profit institutions. Universities often own student and faculty housing, hospitals sometimes own housing for doctors, and churches own monasteries and housing for clergy. If these long-term thinking non-profit organizations have found these structures advantageous, then maybe we can spread this approach to smaller public-benefit organizations through cooperative arrangements. Thus we would be taking a proven idea that works for larger organizations and make it available to smaller ones.

Smaller organizations such as public and private schools, libraries, and independent charitable organizations, could all benefit. A system of shared housing across organizations could also be operated; therefore renters from a variety of different non-profits would live together and could benefit from cross-fertilization. Some success has been found in co-working facilities such as the Tides Center in San Francisco, so extending this to apartment buildings could be seen as a natural next step. Therefore this form of debt-free housing may not be new, but it might now be available to more non-profit organizations than before.

Why Public Benefit Workers?

People that choose to work in non-profit service forego some of potential economic benefits enjoyed by others that are free to make as much money as they can. Salaries tend to be lower in non-profit organizations and furthermore the non-profit organizations cannot be bought; so stock ownership in one’s business is not a potential windfall. With a lack of the mythical ‘pot-of-gold at the end of the rainbow’ for public benefit workers, having a stable and subsidized living environment could be an inducement to attract workers to the sector. Furthermore, much non-profit work is needed when there are economic or other crises in society, so insulating those workers from those ups and downs is important. Otherwise, many public benefit workers could lose their jobs at the same time as the general populace, which would limit the effectiveness of exactly what those workers are there to do. Building an economic system that could expand when the rest is contracting would therefore help balance a cyclical system such as modern business cycle.

Debt Free Housing as form of Endowment

This approach to creating debt-free housing requires some upfront investment and motivation. The potential for long-term stabilizing effect for non-profit organizations can be the same motivation that leads many donors to create endowments. These endowments usually go into a bank to be invested in debt and stock assets, which can create ongoing interest and dividends to the non-profit. Creating debt-free housing can be a more direct form of endowment and one that could return higher and more reliable benefits than financial institution might provide.

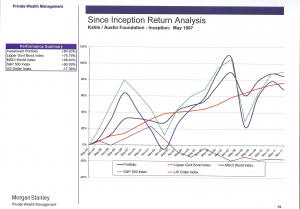

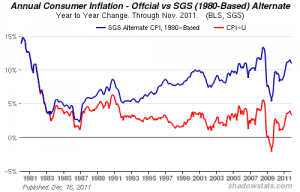

As an example, the return on the holdings of the Kahle/Austin Foundation managed by Morgan Stanley over the last 15 years has returned 4.3% per year on average which is almost 2% over the while the federal rate of inflation over that period of 2.4%[10]. If we use alternative inflation metrics, for instance based on the formulas used by the US government in 1990 or 1980, the inflation rate is 2 to 5% higher making the return for the Foundation possibly less than inflation[11]. This 15-year period has spanned economic cycles and is invested in a way that may be typical for smaller foundations so this return might be representative.

If money during that period had been invested in housing, then for every $1 million in down payment, then it would have bought $5 million in housing in 1996. Even at today’s prices (and therefore ignoring both inflation and the housing boom), this would purchase about 20 housing units of 1000 square feet each in a good neighborhood of San Francisco. If a second mortgage were not taken out, but rather the housing units would be used for employees as a surplus was accumulated, then by one metric, about 5 subsidized units would be available. The other 15 units would still be rented out at market rates to continue paying the mortgage. The units would be worth approximately $2,000 per month, or $24,000 per year, but would be available for 75% less to public benefit employees, which would be an $18,000 benefit per year. Even with only 5 units subsidized at this point, then it would already be worth $90,000 per year in benefit to the non-profits. By the end of the 30-year term, this endowment would be worth $360,000 in benefit per year to the non-profits. While difficult to exactly compare the financial return in a bank account, this level of enduring and direct benefit could motivate donors.

Therefore it could be seen as a good form of endowment for non-profits to invest in local housing for their employees and instead of taking the increase in the endowment as cash from investments.

Potential social impacts

To muse a bit, what might the potential social impacts be of having, say, 5% of city housing be debt-free? These houses might be quite invisible during normal times but during debt crises or recessions, they could serve as an anchor or a stable point for a community in turmoil. With others foreclosing or under large stress, public benefit workers could be in a strong position to provide social services such as healthcare, food, education, and emergency housing.

Furthermore, in times of crises, these organizations might attract new members and copycat organizations. Thus the idea of debt-free life could serve as an active exemplar for others in a way that could cause the system to grow significantly. Similar housing developments could spring up in the same locale and far away in such a way that debt-free housing could spread and develop.

Models of taking single-family houses and making them debt-free could develop as well.[12] Historically people did not move as often, and houses would be paid off and passed down to family members, essentially debt free. If this new system were designed correctly, then we could realize some of those same benefits without restricting people’s movements.

New sources of houses to become debt-free could also come from elderly people that do not intend to pass on all of their wealth. Thus as an alternative to selling one’s house after one dies, one could donate it to a non-profit to manage debt free forever as a form of donation to a cause. Ensuring an enduring legacy, and an associated tax benefit, could be attractive to some people.

By staying removed from direct government funding, these housing units could be immune to conservative swings that tends to sell public assets to private companies. These houses would only depend on the laws of private ownership and therefore could be somewhat resilient from political interference.

Protections from debt more generally could become a point of discussion if this model demonstrates benefits. We might see other types of debt-free environments be created such as debt-free farming, debt-free education, debt-free healthcare, who knows. This subject of debt resistant or debt free organizations may not have been systematically broached since usury stopped being illegal as well as a sin in Europe beginning with the Protestant Reformation. But with the recent financial crisis reminding us of the periodic nature of debt crises, this could be a good the time to create new models.

Since 95% of all money is created by banks by lending money, thus creating both debt and money at the same time, then if we were to move to having significant parts of our lives to be without debt, then the amount of money that is available to be accumulated is diminished. This could have significant and positive effects on limiting the concentration of wealth by a few, thus limiting extreme wealth disparities and the instabilities that follow.

Therefore, creating debt-free housing for public benefit employees seems to be both beneficial and possible. This way we could build some resilience into some of our trusted institutions in the face of economic fluctuations. The idea of living debt-free might even work more broadly to keep a larger part of the population out of debt for some of their necessities. So far, I only know of a small group of people are currently discussing this, and I am posting about it on my blog on at http://brewster.kahle.org. I welcome all input since this seems to be a step worth exploring.

Appendix A:

INTERNET ARCHIVE SCANNER GROUP ECONOMIC STUDY

September 2010

Jordan Modell, pro-bono project

BACKGROUND:

Goal: Try to get a quick reading of the economically based issues and concerns of Scanners earning $12-$14 an hour.

How: Put together a quick questionnaire and spent Monday morning September 20th interviewing 15 workers (13 women and 2 men). The 15 FTE divided into 4 races: Afro American, Central American, Samoan, and Asian. Every person was forth coming, understood why were asking questions and was truly grateful for the study.

LEARNINGS:

1) Lack of community and knowledge. You have people in similar economic circumstances and in many cases the same country, yet there was no knowledge sharing on even basic social services or ways to “get by”. For example transportation costs varied from 8% to 35% of income. With the people paying the least being those who car-pooled (even lower than public transportation).

2) Everyone had a phone and Internet access but only 85% had TV’s. On average people spent $150+ month on Internet/Phone/TV.

3) Rent/Mortgage was the top expense with phone/internet next, then food. Of almost no concern were clothes and of little concern was health care. The former is good news as people have learned how to work the system to buy second hand clothes or share among family. Health Care is of concern as most have no insurance and rely on the republican moto of ‘Just don’t get sick’ as their way of coping. 65% knew where to get free of low cost care when sick but a surprising 35% did not or were not interested.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

SHORT TERM:

Using your size there are a few things you can do immediately that would make a difference in these peoples lives:

1) Foster a sense of community. Throw a guided themed dumpling/pizza parties that will get people to share how they cope with a lack of income. Having more than one may be important as it takes time to foster a sense of sharing across so many races.

- Perhaps one could be on car pooling and you could have sign up sheets, route maps and ideas on parking.

- The second could be on different free health care options. Et Al

2) Use your size to see if you can better cell phone deals that do not expire if someone leaves the Archive. Competition is cut throat in cell phones and they may be able to cut their bills by at least 1/3.

i. Do the same for dental care. Even minimal care like filling cavities.

3) Offer laptops at cost. Most people were concerned with education and 15% actually sent their kids to a type of private school.

LONG TERM:

If you do end up doing a live/work space environment these are things you may wish to consider:

1) Offer free wifi

2) Offer shared cars – similar to zip car

3) Start a mini school

4) Know that people are paying on average $1,250 for accommodation so if you can get this to around $800 you will increase their income by 25% and their disposable income by a factor of 2-4.

Hope this helps.

Best….Jordan

[1] http://www.creditcards.com/credit-card-news/credit-card-industry-facts-personal-debt-statistics-1276.php

[3]https://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/26/us/26hispanics.html?scp=1&sq=median%20net%20worth%20latino&st=cse

[4] A government can help create more positive net-worth households by going into debt itself, but currently the dollar holdings of corporations and other foreign governments is absorbing this surplus thus pushing down the median net worth to close to zero.

[5] http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research/publications/americas-rental-housing-meeting-challenges-building-opportunities

[6] The Internet Archive scanners earn less than 1/3 of the median income of $95,000 thus fall into a category of “extremely low income” renters https://www.efanniemae.com/sf/refmaterials/hudmedinc/hudincomeresults.jsp?STATE=CA and “Fully 63 percent of

extremely low-income renters had severe housing cost burdens

in 2009” http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research/publications/americas-rental-housing-meeting-challenges-building-opportunities, where “Renters with severe housing cost burdens pay more than 50% of household income for rent and utilities.”

[7] Table A5 in http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research/publications/state-nations-housing-2009 (13,615+9,172/75,512 and 2,753+5,215/12,271) and Table A5 in http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/housing/special-topics/files/who-can-afford.pdf

[9] http://aux.zicklin.baruch.cuny.edu/jrer/papers/pdf/past/vol12n01/v12p089.pdf http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_much_does_house_insurance_cost

[10]http://www.inflationdata.com/inflation/Inflation_Calculators/Cumulative_Inflation_Calculator.aspx From May 1997 to November 2011 CPI is 41.31%, or an average of 2.4% per year, and the Kahle/Austin Foundation investments made 86% which comes out to be 4.3% per year, or almost 2% over inflation.

[11] Inflation is calculated by an independent group, from government data, but using the methods from 1990 and 1980 yielding higher inflation numbers: http://www.shadowstats.com/alternate_data/inflation-charts

Pingback: My Blog Experience 1 Year In | Brewster Kahle's Blog

Pingback: Summary of the Debt-Free Housing for Public Benefit Workers Idea, and Responses to Critiques | Brewster Kahle's Blog

Pingback: Putting restrictions on a title to keep a property debt-free may not work well | Brewster Kahle's Blog

Pingback: Non-Financial Endowments for Public-Benefit Organizations | Brewster Kahle's Blog

Pingback: Is there a way to decrease total debt? | Brewster Kahle's Blog