Forty years ago there was a political agenda in the US and much of the world that had merit: fix the issues of ecology, control the expanding power of the multi-national corporations, regulate or phase out nuclear technologies, address the population explosion, and abandon American wars in distant countries. Then why have we seemed to make either little progress or made progress only to see backsliding? Change, when we achieved it, does not seem to stick. Laws were made and then undone. The Environmental Protection Agency was created and then undermined. Another example is AT&T was broken apart, just to re-join again. In the United States we have seen both major parties in power, the electorate evenly split, but little enduring progress on key issues.

I think the answer can be found when we did not achieve structural change for the public benefit.

“Structural change”, in this context, is a re-aligning of forces underlying decision-making. It has the effect of locking in a change thereby making it difficult to undo. Structural change to an industry changes how the actors interact and who does what. Without structural change, things can devolve to their previous status.

“Structural change for the public benefit” would be rule changes on interactions, and these rules are typically set by governments. But we are experiencing a problem. Even democratic governments are no longer responding to public interest as one would expect. This is quite noticeable in the United States.

Equity based corporations, with their unlimited lifetime, can press to restore previous privileges over the course of decades. Politicians in the United States are influenced by those companies that fund the rising campaign expenses, thus making our laws reflect the interests of the companies that can pay the most. Long term pressure from companies can reverse laws that were once thought of as progress on some of our agenda.

So if we can not turn to government for setting rules for public benefit, which is fundamentally their role, what can we do? Turns out there is an example from the technology sector that can hold back some of the corporate forces.

During my career in high-technology the spread of the Internet, Free and Open Source Software, and the World Wide Web have had large scale impacts on industry and culture. But the openness of the Internet is looking shaky based on the failure to secure government support for “net neutrality” thereby allowing infrastructure control to be dominated by a few large corporations. If allowed to run its course, a few companies can determine what new services will be introduced on what terms. This will mean that distribution can be controlled as in the days of the private railroad companies in the United States before Anti-trust legislation broke them up and lead to regulation.

The World Wide Web, an system based on open protocols also has implicit rules of good behavior that has allowed it to grow. In the last 6 years, Google has come to dominate a key unregulated component, search, and then break some of the implicit quid-quo pro between the search engines and websites– a balance where sites would allow to be indexed in return for search services directing users to that site. Google will index others by “crawling” the site and keep the content on their servers for purposes beyond search, and prevent other search engines from crawling their content sites such as Google books and youtube. Other search engines that try to download Google books automatically are locked out, and the same with those trying to index YouTube. So the World Wide Web has not effective regulation to prevent dominant players from hijacking the system.

Free and open source software, however, has an idea that might lead it to have a very long life despite corporate interests interrupting government or fair markets.

Central to free and open source software are licenses which, in turn, are based on copyright. When copyright was expanded to envelop everything expressed in the United States in 1976 via a radical rewriting of copyright law, the effect was an enclosure of ideas. This law granting monopolies to those that never had it, never expected it, nor in many ways wanted it. But because everything expressed was suddenly controlled by someone, it caused communities based on sharing to break. The first dramatic one was in software with the Lisp Machine operating system ceasing to be a community project and an object owned by MIT, which it then sold to a corporation. The result was the software, which was the combined efforts of hundreds over the course of years, died with the short lived company, and one of the authors, Richard Stallman, set out to find a way to keep this waste from happening again. He invented a system-within-the-system– he called it copy-left. It as a set of sharing rules that had the effect of re-establishing some of the freedoms we had before the 1976 copyright law. These sharing rules are fascinating and have been very successful, but the key point here is that a “structural change for public benefit” without government help.

The “structural change for public benefit” brought about by the Free and Open Source licenses and the movement were dependent on the government having made monopoly restrictions very strong. These licenses used the system against itself in a way that a whole industry to, in effect, voluntarily rewrite law. This was painful and slow, but showed it was possible. This system is robust because it only depends on strong monopoly restrictions. If these restrictions were repealed by the government, then we would have most of the freedoms that have been re-established by this scheme. So it works either way.

This is not to say it is desirable. It is much more desirable to have a government that is responsive to public interests. But since this seems to be receding at least in the United States, it is helpful to know that structural change can be enacted that provide relief from extreme laws by leveraging these laws.

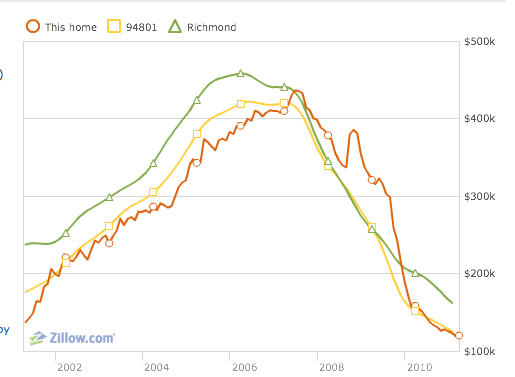

In another article, I will suggest we can create enduring public benefit in housing by leveraging this approach to structural change.